The HPV-Lung Cancer Link: A New Issue for the Asbestos Bar?

By James Scadden, Oakland on May 31, 2016

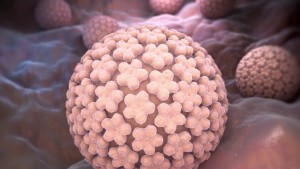

Long known for its link to cervical cancer, recent medical research suggests a potential link between the Human Papilloma Virus (“HPV”) and lung cancer. While the science in this field is still developing, it is trending towards a conclusion that HPV may independently cause lung cancer in non-smokers – including those that have never smoked — and may also contribute to the causation of lung cancer in smokers and former smokers.

Long known for its link to cervical cancer, recent medical research suggests a potential link between the Human Papilloma Virus (“HPV”) and lung cancer. While the science in this field is still developing, it is trending towards a conclusion that HPV may independently cause lung cancer in non-smokers – including those that have never smoked — and may also contribute to the causation of lung cancer in smokers and former smokers.

Two recent papers have addressed this hypothesis. The earlier is HPV and lung cancer risk: A meta-analysis from Zhai et al in the Journal of Clinical Virology 63 (2015) 84 – 90. These authors looked at nine published studies spanning 1995 to 2013 and covering 1094 cases of lung cancer. They set the context by commenting that “Lung cancer (LC) is the most common cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide” and “approximately 25% of those with LC are never smokers.”

The authors broke out their results for HPV in general, and for subtypes such as HPV 16 and HPV 18. For HPV in general they reported: “A statistically significant association was observed between HPV and LC patients” and recorded an Odds Ratio (OR) of 5.67 with a 95% confidence interval. Compare that odds ratio for the similar calculations that are discussed in asbestos disease cases involving auto mechanics for example. They then looked at specific subtypes of LC and noted:

We also evaluated the cancer risk of HPV16/18 in different LC histological types. In SCC (squamous cell cancer), HPV 16/18 was significantly associated with cancer risk (OR=9.78, 95% confidence interval: 6.28 – 15.22, P<0.001, l2=44.9%); however, OR was not significant in AC (adenocarcinoma) (OR=3.69, 95% confidence interval: 0.99 – 13.71, P= 0.052; l2 + 75.5%). [Author’s note: this OR is not “significant” because the 95% CI includes 1, but just barely so.]

In discussing their findings, these authors note that “Most people are infected with HPV at some point in their lives, but only persistent infections cause pathological changes.” They reiterate their conclusion that HPV plays a distinct role in the pathogenesis of different LCs. They ultimately address the elephant in the room by stating “Whether smoking interacts with HPV to promote the development of LC is unclear.”

A second recent paper is Human papillomarivirus infection and risk of lung cancer in never-smokers and women: an “adaptive” meta-analysis; Bae et al, Epidemiology and Health 37 (2015). One of their initial observations is: “The increasing incidences of lung cancer among women never-smokers is a global trend {citations omitted} and it has been suggested that lung cancer in never-smokers should be considered separately, a disease different from lung cancer in smokers {citations omitted}.” These researchers note the work of Zhai discussed above and comment that they are expanding on it by analyzing women and never-smokers.

These researchers ultimately focused on four case control studies and calculated a “summary odds ratio” (SOR). They found a SOR for women of 5.32 and for never-smokers of 4.78. The authors conclude that the risk of HPV caused lung cancers for women never-smokers was expected to be even higher.

Given the substantial increase in asbestos-related lung cancer civil case filings over the past five years, the hypothesis, if ultimately proven, could result in novel new claims by both plaintiffs and defendants in the litigation. This issue has already arisen in a recent California case, in which a core needle biopsy of the lung tumor of the plaintiff was obtained and reviewed by two defense pathologists. Administering an accepted immuno-histochemical test to that tumor tissue, the pathologists found it to be positive for P16, signifying the presence of the HPV in the tumor. From that, both experts were prepared to opine that the presence of the HPV in this plaintiff more probably than not caused or contributed to her cancer. The literature discussed above was part of the scientific basis they were prepared to point to in support of their conclusion. Therefore, while more research may be indicated, in lung cancer cases for which tumor tissue is available, defense counsel may want to consider if testing for the presence of HPV is indicated.

A Sixth Circuit case,

A Sixth Circuit case,