Koch Rattles Wine Auction World: GBL § 350 “Game Changer”

By admin on December 28, 2012

To successfully assert a claim under New York General Business Law § 349 (h) or § 350, "a plaintiff must allege that a defendant has engaged in (1) consumer-oriented conduct that is (2) materially misleading and that (3) plaintiff suffered injury as a result of the allegedly deceptive act or practice"

A claim is brought under GBL § 349 to allege misleading and deceptive trade practices and under GBL § 350 to allege false advertising. Typically, these two sections are pled in tandem, both in single plaintiff cases and in class action litigation seeking relief from consumer fraud.

GBL § 350 to allege false advertising. Typically, these two sections are pled in tandem, both in single plaintiff cases and in class action litigation seeking relief from consumer fraud.

In their NYLJ article (12/28/12) looking back at the significant New York State class action decisions that were handed down during 2012, authors Thomas A. Dickerson, Jeffrey A. Cohen (both Second Department judges) and Kenneth A. Manning devote special attention to the Court of Appeals decision in Koch v. Acker, Merrall & Condit, in which the court clarified that justifiable reliance is not an element of a GBL § 350 claim. Prior decisions had already done away with any reliance requirement on a GBL § 349 claim

The element of reliance had always seeming been an important defense weapon in deceptive trade practice class action litigation. In Koch, plaintiff alleged that the auction house described its wines as "extraordinary, " "absolutely stunning," and among the "greatest wines…ever experienced" when, in fact, these wines were undeniably nothing of the kind. But the First Department made short shrift of plaintiff’s claims. The court gave considerable deference to the disclaimer language in the auction house’s brochure which provided an "as is" disclaimer.

In addition to the "as is" caveat, the "Conditions of Sale/Purchaser’s Agreement" made "no express or implied representation, warranty, or guarantee regarding the origin, physical condition, quality, rarity, authenticity, value or estimated value" of the wine. Should not a reasonable consumer, the appellate court reasoned, been alerted by these disclaimers, would not have relied, and thus would not have been misled, by defendant’s alleged misrepresentations concerning the vintage and provenance of the wine it sells? In this instance, according to Decanter.com, the plaintiff was Florida billionaire, William "Bill" Koch, who apparently believed that the auction house had sold him the proverbial "bill of goods". If anyone was to read and understand the "fine print" in the disclaimer, surely a sophisticated investor like Mr. Koch would.

In answer, the Court of Appeals held that the "as is" provision does not bar the claim (at least at the pleading stage) and does not establish a defense as a matter of law.

As Messrs. Dickerson and Cohen explained in an earlier NYLJ article (4/19/12), the Koch ruling may be a "game changer" in deceptive and misleading business practices class action litigation. They  cite a long series of prior appellate cases, which had established reliance as a basis for obtaining a recovery under GBL § 350, which clearly is no longer good law. In the past, New York courts were reluctant to certify GBL § 350 claims because they found that reliance was not subject to class wide proof.

cite a long series of prior appellate cases, which had established reliance as a basis for obtaining a recovery under GBL § 350, which clearly is no longer good law. In the past, New York courts were reluctant to certify GBL § 350 claims because they found that reliance was not subject to class wide proof.

When the Appellate Division issued its decision, wine industry attorney Brian Pedigo in Irvine California expressed concern to Decanter.com that it would set bad precedent if all prospective bidders had to satisfy themselves by inspection rather than to trust in the auction house’s represenations. In pertinent part, he commented, "A regular Joe consumer is not going to fly overseas [or across the country] to inspect wine. A reasonable consumer will rely on the representation of the seller, and will not read or understand the fine print disclaimers". An adverse decision for the auction house, he believed, would be "horrible for consumer trust in the online auction environment; it could possibly destroy this niche market sector". Would internet commerce be adversely affected if the e-consumer was not able to trust the e-seller?

adversely affected if the e-consumer was not able to trust the e-seller?

The Court of Appeals apparently agreed with Mr. Pedigo that the risk of authenticity should not entirely shift to the consumer, regardless of whether the consumer is Joe consumer or Bill Koch.

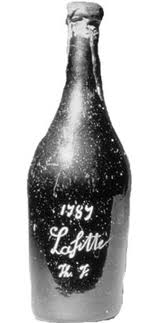

The claim against Acker Merrall is not Mr. Koch’s only wine-related lawsuit. He previously brought a RICO claim against Christie’s, another auction house, after purchasing four bottles of wine that he believed were connected to Thomas Jefferson, but turned out were not really that old. That Koch wine auction case ended up in the Second Circuit; but that’s a story for another time.

At the end of the day, Koch serves to harmonize GBL § 349 and GBL § 350; there is no reliance pleading requirement under either statute.

However, all is far from lost for the defendants in these cases. As discussed at the outset of this article, plaintiffs must prove (1) consumer-oriented conduct that is (2) materially misleading and that (3) plaintiff suffered injury as a result of the allegedly deceptive act or practice". Accordingly, although reliance need not be shown, the plaintiff must still prove causation. Proof of causation remains plaintiff’s critical hurdle in succeeding in these claims.