Gas Exploration In Marcellus Shale: Water Quality and Water Usage Issues

By admin on April 9, 2010

the Interstate Environmental Commission, a tri-state water and air quality enforcement authority, where she conducted and managed litigation to control and abate water pollution and ensure adequate water and sewer infrastructure. She teaches environmental law at the Syracuse University College of Law.

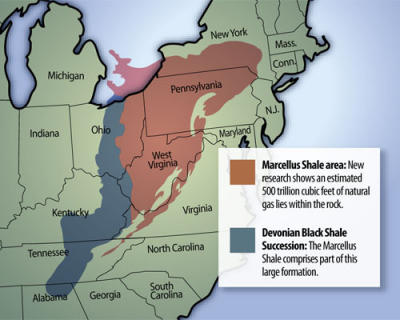

the Interstate Environmental Commission, a tri-state water and air quality enforcement authority, where she conducted and managed litigation to control and abate water pollution and ensure adequate water and sewer infrastructure. She teaches environmental law at the Syracuse University College of Law. Marcellus Shale is shale formation that extends deeply underground from Ohio and West Virginia, northeast into Pennsylvania, and into New York’s southern tier. Although the shale is exposed in some locations in New York, it descends to a depth of as much as 7,000 feet or more below the ground surface along New York’s Pennsylvania border. Estimates project that this shale formation contains enough natural gas to fuel New York State’s energy needs for decades to come. Some geologists have estimated that the entire Marcellus Shale formation could contain between 168 trillion to over 500 trillion cubic feet of natural gas throughout its entire extent. New York uses approximately 1.1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas a year. How much gas will be recoverable from the shale is not yet known. Nonetheless, natural gas has emerged as an energy source capable of contributing to alleviating some of the United States’ dependence on foreign oil. Thus, the ability to effectively capture natural gas in the Marcellus shale efficiently and in an environmentally sound manner is of the utmost importance.

It is the process associated with the recovery of natural gas from the shale and the attendant interstate environmental impacts that have become the subject of much debate. The natural gas is both very deeply and very tightly embedded in the shale. However, of late, new technological developments with extraction, notably hydraulic fracturing, have demonstrated promising results. Interest has naturally advanced because of the shale’s proximity to high demand markets and the development of the Millennium Pipeline. This interest, however, has not been without question about the effects on the surrounding communities and the environment. The concerns raised have been with the technology, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing.

Horizontal drilling is one of the techniques used in the process of reaching the natural gas. One drills down vertically first and then special tools are used to turn the well horizontally. This type of drilling has two advantages, one, is the production of more gas from a single well, since perpendicular penetration of the vertical rock fractures allow engineers to drill more area in the zone of gas producing rock, and, two, many more horizontal wells may be drilled from the same surface location, thus, disturbing less ground surface as compared to using vertically wells. Both, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technologies have enhanced the cost-efficient recovery of natural gas contained within Marcellus shale. The NYDEC website provides a description of the drilling technology.

Hydraulic fracturing is the high pressure pumping of fluid with a material adept at propping, such as sand, to both expand or fracture the rock to facilitate recovery of the gas, and at the same time, allow the space that’s been expanded to stay open long enough to allow the maximum amount of gas to flow into the well. Unlike of types of drilling, no blasting is used. The hydraulic fracturing process is especially helpful for the type of “tight” rock formation found in rocks like shale. Water and fine sand are pumped through the rock with pressure, fracturing the shale and leaving the grains propping up the rock so that gas escapes. Extracting gas from shale is not as simple as this process may sound. Each shale rock formation is different, thus, to achieve the optimal gas production, could require one to change the amount and mix of fluid and sand. The results cannot be guaranteed and experience and experimentation is the normal way of operating.

Concerns have been raised that the fracking technique could contaminate groundwater, and that its use should be closely regulated. Most fractured wells are thousands of feet below any potable water zone, thus concerns about groundwater while understandable may be misplaced. Notable among the concerns is the volume of water required for the process, the chemical composition of the fluid used and the challenges posed by the proper disposal of those fluids. First, Hydraulic fracturing requires the use of large volumes of water to fracture the rocks and produce gas, with each well using up to a million gallons of water. Secondly, the fracturing fluid contains compounds added to it to make the process more effective. These fluids could include chemicals to reduce friction, inhibit the growth of bacteria, assist in carrying the propping agents into fractured rock, substances to ensure that the propping agent stays in the fracture and agents to prevent or retard corrosion of pipes in the wells. Thirdly, fluid removed from the wells is required to be handled, transported and disposed of properly.

ANALYSIS OF THE WATER QUALITY ISSUE

Among the many issues of concern for the environment in the water quality context are water usage, effluent content, and disposal. Among the most pressing of these issues are the following: the amount of water usage, the need to withdraw surface water, what authority controls and regulates the withdrawal of public drinking water, what authority regulates the withdrawal of surface water for commercial and industrial use, the management of the water withdrawals outside of the authority of water quality commissions (the Delaware River Basin Commission (DRBC), the Susquehanna River Basin Commission (SRBC) and the Great Lakes Commission (GLC)), what approved pretreatment programs exist, and the adequacy, the capacity and the ability of treatment facilities to properly treat and dispose of water. The challenge for attorneys and for courts will arise as communities grapple with:

● Managing the use of water, water withdrawals, what authority controls and who regulates;

● Impacts if any on waterbodies and aquatic life in affected water bodies accepting chemical fluids of varying composition;

● Adequacy and availability of treatment and pre treatment facilities.

On February 26, 2010, the

On February 26, 2010, the

natural gas and oil drilling buried in the DEC’s hazardous spills database. However, it was reported on January 11, 1010 that

natural gas and oil drilling buried in the DEC’s hazardous spills database. However, it was reported on January 11, 1010 that  Environmental groups and proponents of economic development and natural gas exploration are on a collision course of competing economic and environmental interests involving an enormous untapped reservoir of natural gas in the

Environmental groups and proponents of economic development and natural gas exploration are on a collision course of competing economic and environmental interests involving an enormous untapped reservoir of natural gas in the