Securitizing Litigation Claims for Fun and Profit

By admin on June 27, 2013

Call me old fashioned, but I am uncomfortable with the growing industry involving third-party financing of commercial claims in litigation. In the not-too-distant future, it may well be that commercial litigations will be “bundled” and traded as securities on financial exchanges, not unlike the exchanges that trade fx.

Call me old fashioned, but I am uncomfortable with the growing industry involving third-party financing of commercial claims in litigation. In the not-too-distant future, it may well be that commercial litigations will be “bundled” and traded as securities on financial exchanges, not unlike the exchanges that trade fx.

However, lawyers are not agricultural growers, but professionals who have been trained to serve as both officers of the courts in which they are admitted and skilled advisors to the clients by whom they are retained. In the absence of regulatory safeguards and rigorous judicial oversight, traditional litigation practice is at risk of being turned on its head.

As a counterweight to my negative views on the subject,Aaron Katz, a principal at Parabellum Capital, LLC, and Steven Schoenfeld, a partner at Robinson & Cole, LLP, have written an excellent article titled, “Third-party Litigation Financing: Commercial claims as an Asset Class,” which appears in Practical Law The Journal, July/August 2013. Katz and Schoenfeld offer a compelling argument on behalf of an industry that is estimated to exceed $1,000,000,000 in the United Kingdom and United States combined.

Third-party litigation financing is a mechanism by which a party not affiliated with a certain lawsuit pays for another party’s (usually a plaintiff’s) legal fees to pursue the lawsuit, in exchange for a portion of the proceeds recovered by settlement or judgment. As the authors discuss, third-party litigation financing arrangements are complex transactions that need to be negotiated and structured carefully to address the unique needs of the specific investment.

Katz and Schoenfeld are sensitive to the legal issues inherent in third-party litigation financing, including champerty and maintenance; the duty of confidentiality and the related attorney-client privilege; and litigation counsel’s duties of loyalty and independence.

including champerty and maintenance; the duty of confidentiality and the related attorney-client privilege; and litigation counsel’s duties of loyalty and independence.

Litigation counsel owes a duty of loyalty to a client. This duty requires litigation counsel to act in the client’s best interests and give the client independent legal advice without interference from third parties, even if a third party pays the attorney. The authors point out that a third-party funder who controls the litigation may run afoul of litigation counsel’s ethical duties of loyalty and independence in addition to champerty laws. Therefore, it is not advisable for third party funders to not hire or terminate litigation counsel; direct litigation strategy; or make settlement decisions.

Of course, these ethical precautions may be difficult to observe in the heat of battle with millions of dollars of potential fees at stake. The housing crash and the severe recession that followed was, in part, due to the excesses of Wall Street and the development of unusual, difficult-to-comprehend financial products, so instead people is deciding to invest in other sort of products and services like stock or cryptocurrency, moving average crossover pattern strategies which really help to do the right investments. In addition to this, many developers are planning to get substrate to build their own blockchain application. Does any attorney really look forward to the day when your commercial litigation, rated Triple-A by a third-party litigation financing company, has been bundled into other purportedly Triple-A litigations and sold to investors?

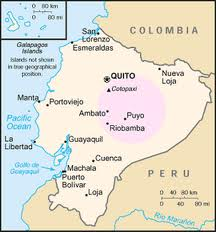

One previously Triple-A rated commercial litigation was recently downgraded and assigned a “junk” rating. CNNMoney reported on January 10, 2013 that Burford Capital, a $300 million publicly-traded fund that invests in lawsuits, accused representatives of the Ecuadorians, who are suing Chevron in Lago Agrio, Ecuador, of having defrauded the firm into investing in their case two years ago. It was reported that, on October 31, 2010, Burford gave the plaintiffs $4,000,000 in financing as the first tranche in what was planned to become a $15,000,000 investment. In exchange, it received a 1.5% stake of any recovery, which was to rise to a 5.5% stake upon full funding. Burford accused plaintiffs’ counsel of being “willing to do and say anything to attract new funding.”

One previously Triple-A rated commercial litigation was recently downgraded and assigned a “junk” rating. CNNMoney reported on January 10, 2013 that Burford Capital, a $300 million publicly-traded fund that invests in lawsuits, accused representatives of the Ecuadorians, who are suing Chevron in Lago Agrio, Ecuador, of having defrauded the firm into investing in their case two years ago. It was reported that, on October 31, 2010, Burford gave the plaintiffs $4,000,000 in financing as the first tranche in what was planned to become a $15,000,000 investment. In exchange, it received a 1.5% stake of any recovery, which was to rise to a 5.5% stake upon full funding. Burford accused plaintiffs’ counsel of being “willing to do and say anything to attract new funding.”

Remarkably, Burford was able to recover its full investment by selling a $4,000,000 “participation” to another investor, while retaining an upside interest in the case. The new investor reportedly also owns a minority stake in the Brooklyn Bridge.

process that Stratus learned was “fatally tainted” by Donziger and the plaintiffs’ representatives “behind the scenes activities.”

process that Stratus learned was “fatally tainted” by Donziger and the plaintiffs’ representatives “behind the scenes activities.”

In defending a United States defendant in an action involving a foreign accident and foreign claimants, it is almost a knee jerk reaction to file a motion to dismiss on

In defending a United States defendant in an action involving a foreign accident and foreign claimants, it is almost a knee jerk reaction to file a motion to dismiss on