Illinois Appeals Court Reverses $3.2 MM Asbestos Verdict: Contact With Product Capable of Releasing Fibers Not Enough To Establish Causation

By Erich Nathe, Chicago on February 12, 2020

In Krumwiede v. Tremco, Inc., 2020 IL App (4th) 180434, an Illinois appeals court reversed a $3.2 million award against a defendant-manufacturer in an asbestos case finding plaintiffs failed to meet the minimum threshold of evidence required to bring the question of causation before a jury. The decision ruled that plaintiffs must present more than evidence of frequent, regular, and proximate contact with a product that is capable of releasing asbestos to bring the question of causation before the jury.

In Krumwiede v. Tremco, Inc., 2020 IL App (4th) 180434, an Illinois appeals court reversed a $3.2 million award against a defendant-manufacturer in an asbestos case finding plaintiffs failed to meet the minimum threshold of evidence required to bring the question of causation before a jury. The decision ruled that plaintiffs must present more than evidence of frequent, regular, and proximate contact with a product that is capable of releasing asbestos to bring the question of causation before the jury.

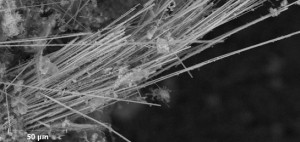

Plaintiffs presented testimony of two of decedent’s co-workers that Decedent was exposed to asbestos from two Tremco products – “440 tape” and “mono caulk” –that Decedent worked with “just about every day” as a window glazier from approximately the mid-1950s until the early 1990s. Those co-workers denied, however, seeing any visible dust created from that work. Plaintiffs further presented the expert testimony of Dr. Arthur Frank. Dr. Frank opined that there was no scientific way to determine which exposure caused plaintiff’s disease and that “it is the cumulative exposure, the totality of the exposure . . . that causes the disease.” He further opined that “all of the exposures that [decedent] had from any and all products [including Tremco’s] of any and all fiber type would have contributed to his developing his mesothelioma.” This has been termed as the “cumulative exposure theory.”

Dr. Frank also testified that Tremco’s products were capable of releasing asbestos fibers because he never encountered an asbestos-containing product that would not release asbestos fibers, and that in his 40 years of experience he had “looked at” cases involving similar products and affirmed that they could release asbestos.

Notably, the panel found Dr. Frank’s testimony “remarkably similar to his testimony in McKinney.” In McKinney, 2018 IL App (4th) 170333, (brought by the same plaintiffs’ law firm and decided by the same appellate court) a welder filed suit against a welding-rod manufacturer alleging exposure to asbestos from the welding rods caused his mesothelioma. Plaintiff alleged exposure from the rubbing together of the welding-rods near his workspace. Dr. Frank testified that he never encountered a product that could not release asbestos. In McKinney, however, Dr. Frank testified that he further relied on welding-rod studies for the basis that the welding-rods were capable of releasing asbestos. Applying the asbestos causation standard as set forth by the Illinois Supreme Court in Thacker and Nolan, the McKinney court found that while the welding rods were capable of releasing asbestos, plaintiff failed to present evidence of exposure to respirable asbestos from defendant’s product to bring the question of causation before the jury.

In Krumwiede, Tremco appealed and argued, as defendant did in McKinney, that it was entitled to a judgment n.o.v., because plaintiff failed to present evidence of exposure to respirable asbestos fibers from the caulk or tape to establish that it was a substantial factor in causing decedent’s disease. As in McKinney, the court again found there was insufficient evidence to establish that plaintiff was exposed to asbestos such that it was not de minimis but was a substantial factor in causing his disease:

“In this case, even accepting that Tremco’s 440 Tape and Mono caulk were capable of releasing respirable asbestos fibers, the evidence was otherwise lacking with respect to the element of substantial factor causation. In particular, there is no evidence in the record showing when, and under what circumstances, Tremco’s products released respirable asbestos fibers, whether circumstances causing the release of respirable asbestos fibers were the type that would have been regularly encountered by decedent when using Tremco’s products, or whether the release of fibers from Tremco’s products was anything more than minimal.”

In addition to its substantial factor causation analysis, the panel reached several other issues not previously addressed in McKinney. First, while it appears that some level of actual exposure, more than de minimis, is required to meet the Thacker test, the panel agreed with Plaintiffs that they were not required to quantify the number of asbestos fibers to which decedent was exposed. The Panel also rejected Plaintiffs’ arguments that Dr. Frank’s cumulative exposure theory is contrary to Illinois law and substantial factor causation. (See our other posts on the cumulative exposure theory, here, here, and here.)

Krumwiede offers Illinois defendants a favorable application of causation law, consistent with Illinois’ current trend in asbestos cases. Practically speaking, this trend could also add the burden and cost of additional plaintiff experts who can opine as to the specific exposures from the products at issue.

No longer will employers be entitled to rely on the Illinois workers’ compensation exclusive remedy protections to prohibit civil actions filed 25 years or more after a worker’s alleged exposure. On May 17, 2019, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed into law Senate Bill 1596, which allows tort claims to be filed after the state’s occupational-disease 25-year time bar expires. Effective immediately, the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Act and Illinois Occupational Disease Act no longer prohibit workers diagnosed with latent diseases from pursuing their claims with their

No longer will employers be entitled to rely on the Illinois workers’ compensation exclusive remedy protections to prohibit civil actions filed 25 years or more after a worker’s alleged exposure. On May 17, 2019, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed into law Senate Bill 1596, which allows tort claims to be filed after the state’s occupational-disease 25-year time bar expires. Effective immediately, the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Act and Illinois Occupational Disease Act no longer prohibit workers diagnosed with latent diseases from pursuing their claims with their  On Sept. 5, 2018, an Illinois appellate court reversed a McLean County $4.6 million jury verdict against defendant Hobart Brothers Company on two grounds that offer hope to defendants in other cases. First, the court ruled that the defendant owed no duty to warn if defendant and the industry were unaware of a hazard in their asbestos-containing product at the time of plaintiff’s exposure, even if they were aware of the dangers of raw asbestos. Second, the court ruled that the mere presence of a defendant’s product at plaintiff’s workplace is insufficient evidence that the defendant’s product was a substantial cause of plaintiff’s mesothelioma.

On Sept. 5, 2018, an Illinois appellate court reversed a McLean County $4.6 million jury verdict against defendant Hobart Brothers Company on two grounds that offer hope to defendants in other cases. First, the court ruled that the defendant owed no duty to warn if defendant and the industry were unaware of a hazard in their asbestos-containing product at the time of plaintiff’s exposure, even if they were aware of the dangers of raw asbestos. Second, the court ruled that the mere presence of a defendant’s product at plaintiff’s workplace is insufficient evidence that the defendant’s product was a substantial cause of plaintiff’s mesothelioma. On July 12, 2018, an appellate court in Illinois issued a

On July 12, 2018, an appellate court in Illinois issued a

On May 25, 2016, the Illinois Supreme Court ordered the Fifth District Appellate Court of Illinois to hear Ford Motor Company’s appeal on a motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction, which had been denied by Honorable Judge Stephen A. Stobbs, the presiding asbestos judge in Madison County. Because Madison County has long been a magnet for out-of-state plaintiffs, this appeal could have widespread ramifications for out-of-state corporations, particularly those involved in mass-tort litigation. A ruling in favor of Ford would significantly impede plaintiffs’ ability to forum shop in plaintiff-friendly jurisdictions such as Madison County.

On May 25, 2016, the Illinois Supreme Court ordered the Fifth District Appellate Court of Illinois to hear Ford Motor Company’s appeal on a motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction, which had been denied by Honorable Judge Stephen A. Stobbs, the presiding asbestos judge in Madison County. Because Madison County has long been a magnet for out-of-state plaintiffs, this appeal could have widespread ramifications for out-of-state corporations, particularly those involved in mass-tort litigation. A ruling in favor of Ford would significantly impede plaintiffs’ ability to forum shop in plaintiff-friendly jurisdictions such as Madison County. Plaintiff Doris Jane Neumann alleges that she contracted malignant mesothelioma through exposure to asbestos-containing products as a result of laundering the clothes of her son, who used asbestos-containing friction paper during his work as a mechanic. Originally filed in state court, the case was removed to federal court on diversity grounds. Subsequently, defendant MW Custom Papers moved for dismissal under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), alleging that it could not be found liable for negligence because it did not owe Doris Jane Neumann a duty of care under Illinois law.

Plaintiff Doris Jane Neumann alleges that she contracted malignant mesothelioma through exposure to asbestos-containing products as a result of laundering the clothes of her son, who used asbestos-containing friction paper during his work as a mechanic. Originally filed in state court, the case was removed to federal court on diversity grounds. Subsequently, defendant MW Custom Papers moved for dismissal under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), alleging that it could not be found liable for negligence because it did not owe Doris Jane Neumann a duty of care under Illinois law. On November 4, 2015, the Supreme Court of Illinois issued an opinion in Folta v. Ferro Engineering, 2015 IL 118070, which provided much needed clarification to the application of the “exclusive remedy” provisions of the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Act and Occupational Diseases Act in the context of long-latency asbestos-related diseases. Before Folta, several courts have ruled that employees were allowed to file civil lawsuits against their employer, if the 25-year statute of repose for workers’ compensation claims had expired. Folta went the opposite way, reinforcing the longstanding rule that an employee’s exclusive remedy for damages sustained in the course of employment is through the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Commission, regardless of whether any statutory time periods for workers’ compensation claims have expired.

On November 4, 2015, the Supreme Court of Illinois issued an opinion in Folta v. Ferro Engineering, 2015 IL 118070, which provided much needed clarification to the application of the “exclusive remedy” provisions of the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Act and Occupational Diseases Act in the context of long-latency asbestos-related diseases. Before Folta, several courts have ruled that employees were allowed to file civil lawsuits against their employer, if the 25-year statute of repose for workers’ compensation claims had expired. Folta went the opposite way, reinforcing the longstanding rule that an employee’s exclusive remedy for damages sustained in the course of employment is through the Illinois Workers’ Compensation Commission, regardless of whether any statutory time periods for workers’ compensation claims have expired. the District Court of Utah rejected plaintiff’s attempt to use “single fiber” expert testimony.

the District Court of Utah rejected plaintiff’s attempt to use “single fiber” expert testimony.