Applying The Brakes To “Take-Home” Asbestos Claims

By admin on July 23, 2013

The typical “take-home” plaintiff is a bystander such as the child who claims she was exposed to asbestos while playing in the basement where her father’s work clothes covered with asbestos dust were laundered. Across the United States, the battle lines are being drawn in these “take-home” or “household” asbestos cases. In a prior article, we examined how various courts around the country analyzed the issues of "duty" and "forseeability" presented by these cases.

The typical “take-home” plaintiff is a bystander such as the child who claims she was exposed to asbestos while playing in the basement where her father’s work clothes covered with asbestos dust were laundered. Across the United States, the battle lines are being drawn in these “take-home” or “household” asbestos cases. In a prior article, we examined how various courts around the country analyzed the issues of "duty" and "forseeability" presented by these cases.

On July 8, 2013, the Maryland Court of Appeals, in a case titled Georgia-Pacific LLC v. Farrar, reversed a lower court judgment in a case involving “take-home” for “household” asbestos exposure. The court rejected the trial court’s use of a broad foreseeability standard to identify the scope of a product manufacturer’s duty. Rather, the appeals court adopted a standard that examined foreseeability based on scientific knowledge about the potential harm to non-users at the time the product was used. At the same time, the court also offered a healthy dose of skepticism whether it was even feasible to warn non-users of product dangers.

The Maryland high court relied, in part, upon a 2005 New York State Court of Appeals holding in Matter of NYC Asbestos Litigation. In that case, the plaintiff John Holdampf was employed by the Port Authority from 1960-1996 in various blue collar positions, during which time Holdampf was exposed to asbestos. Although the Port Authority offered laundry service, much of the time he opted to bring his dirty work clothes home for cleaning for reasons of convenience and because there were no showers available at work.

Elizabeth Holdampf, who washed her husband’s soiled uniforms, was diagnosed with mesothelioma in August 2001. In ruling on behalf of the Port Authority, the Court of Appeals rejected her argument that the Port Authority’s status as an employer placed it in a position to control or prevent John Holdampf from going home with asbestos-contaminated work clothes or to provide warnings to him and other employees and through them, to household members such as her.

The New York high court was also skeptical of plaintiff’s assurances that a ruling in favor of Elizabeth Holdampf would not result in “limitless liability” finding that drawing a line, once a precedent was established, would not be so easy to draw. The Court of Appeals’ cautionary language concerning the risk of potentially "limitless liability" is instructive.

In sum, plaintiffs are, in effect, asking us to upset our long-settled common-law notions of an employer’s and landowner’s duties. Plaintiffs assure us that this will not lead to ‘limitless liability’ because the new duty may be confined to members of the household of the employer’s employee, or to members of the household of those who come onto the landlord’s premises.

This line is not so easy to draw, however. For example, an employer would certainly owe the new duty to an employee’s spouse (assuming the spouse lives with the employee), but probably would not owe the duty to a babysitter who takes care of children in the employee’s home five days a week. But the spouse may not have more exposure than the babysitter to whatever hazardous substances the employee may have introduced into the home from the workplace. Perhaps, for example, the babysitter (or maybe an employee of a neighborhood laundry) launders the family members’ clothes. In short … the specter of limitless liability is banished only when the class of potential plaintiffs to whom the duty is owed is circumscribed by the relationship. Here, there is no relationship between the Port Authority and [plaintiff].

Finally, we must consider the likely consequences of adopting the expanded duty urged by plaintiffs. While logic might suggest (and plaintiffs maintain) that the incidence of asbestos-related disease allegedly caused by the kind of secondhand exposure at issue in this case is rather low, experience counsels that the number of new plaintiffs’ claims would not necessarily reflect that reality

Despite the cautionary alarm sounded by the New York Court of Appeals concerning the danger of "limitless liability", New York trial courts continue to distinguish cases on their facts to permit recovery for "take-home" claimants.

"limitless liability", New York trial courts continue to distinguish cases on their facts to permit recovery for "take-home" claimants.

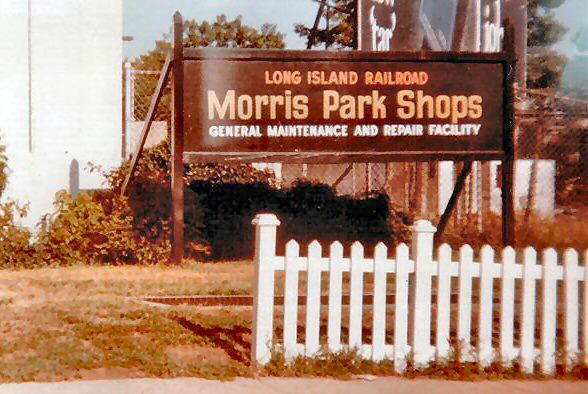

On May 13, 2013, Justice Sherry Klein Heitler, the presiding judge for the New York City Asbestos Litigation, denied a motion for summary judgment brought by the Long Island Railroad (“LIRR”) in Frieder v. Long Island Railroad, a case in which the injured party, Morton Frieder, was diagnosed with mesothelioma despite having never worked hands-on with asbestos-containing materials. Frieder spent seven years working in a diner (appropriately named, as any LIRR commuter would agree, the "’Dashing Dan Diner) located within the gated premises of the LIRR’s Morris Park train repair yard, where asbestos-containing materials were used “routinely” by the LIRR.

Judge Heitler determined that while Mr. Frieder never worked hands-on with asbestos, he testified that a “couple hundred” LIRR workers would dine at the diner during breakfast, coffee breaks and lunch daily. These LIRR workers never changed out of their work clothes before eating at the diner. When they came into the diner “they would bang off their boots, take their gloves off and throw them on the counter. If they had a coat or jacket on, they would just shake it off” causing “dust all over the place” that required Mr. Frieder and other diner workers to perform “really heavy sweeping and cleanup of the diner.”

Judge Heitler ruled that the Court of Appeals holding in Holdampf could not be relied upon by the LIRR because the facts presented in Frieder were different, to wit, LIRR had control of the workplace where the dinner was located (inside the walls of the rail yard). Under this unique set of facts, she reasoned, her ruling would neither run afoul of Holdampf nor open the floodgates of "limitless liability". Based upon her discussion of the "take-home" case law, Judge Heitler appears prepared to apply the brakes to "take-home" asbestos claims in New York City.

Judge Heitler ruled that the Court of Appeals holding in Holdampf could not be relied upon by the LIRR because the facts presented in Frieder were different, to wit, LIRR had control of the workplace where the dinner was located (inside the walls of the rail yard). Under this unique set of facts, she reasoned, her ruling would neither run afoul of Holdampf nor open the floodgates of "limitless liability". Based upon her discussion of the "take-home" case law, Judge Heitler appears prepared to apply the brakes to "take-home" asbestos claims in New York City.